Business travellers expect a lot from their laptop but a trio of tightly connected features tops the list. The ideal notebook should be thin, it should be light and it should have enough battery life to last a whole day and then some.

The first two traits naturally go together and they’re ideal for maximising space in your carry-on bag as well as taking from one client meeting to the next meeting. And being able to use the laptop at your airline’s departure lounge, during an international flight and still being able to do a quick email session at the airport while waiting for your bags to hit the carousel? That seals the deal.

So when will you be able to get a laptop that’s made for the long haul? When can you hit the road but leave the AC adaptor at home?

The answer to that question is today, depending on the price you’re prepared to pay and sometimes the compromises you’re willing to make. Some netbooks easily strut past the 10-hour mark but they lack the muscle, features and capabilities of a fully fledged laptop.

In some cases you can add a secondary battery which replaces the notebook’s CD/DVD drive or attaches to the notebook’s underside (this type of battery is sometimes called a ‘travel slice’) so you can hit the road with two full tanks of juice – although this adds to the laptop’s bulk.

But within the next few years that won’t even be an issue. The ever-onwards march of technology in computer chips and other components will make ‘all day computing’ a trait of almost every laptop.

“The challenge for us is to bring all-day battery life to the mainstream so that you take the laptop to work and leave the power supply at home,” says Mooly Eden, general manager of Intel’s Mobile Platforms group.

“But ‘all day’ means different things to different people,” Eden tells Dynamic Business. “For me it might be eight hours, for you it might be 10 hours. And we need to do even more than that, because as the laptop gets older the battery life will slowly get lower.”

Eden’s goal for Intel? “We need to deliver 10-to-12 hours without the charger. And we will be able to do that, because all-day battery life is not just possible, it is inevitable.”

The foundations are already in place. Intel’s family of Core i3, Core i5 and Core i7 chips perform the neat trick of running faster than any previous generation of Intel silicon while drawing less power from the battery. And even that dollop of extra speed is being channelled into eking out extra battery life.

If you divide the laptop’s typical working day into tiny slices of time, most of that day is spent in varying states of idle rather than being actively used. More processing muscle means the notebook can do the heavy lifting faster so that it more quickly returns to the low-power idle state – and the more time it spends there, the longer the battery lasts.

Eden calls this feature “hurry up and get idle”, and it’s enhanced by ‘turbo boost’ modes which further accelerate the processor for short but intense bursts. These can be everyday tasks like opening an email attachment or previewing a PowerPoint deck as a set of thumbnails. Tasks that take six seconds suddenly take three or four: but it’s less about speed than sleep.

“The idea is wake the notebook up, do the job and then go to sleep again,” Eden explains. “If the chip does the job faster it can go back to sleep sooner, so you get better performance and you also get extended battery life. This is the real secret of energy efficiency.”

Yet the processor is just one part of the notebook. The screen is responsible for the largest portion of a laptop’s power drain, followed by the hard drive. Dramatic efficiencies in these areas are slower to come, with fewer breakthroughs and smaller leaps.

That said, notebook screens with LED backlighting draw less juice than the non-backlit models while also providing a brighter picture. And while ‘solid state drives’ (SSDs) draw almost no power compared to the conventional and battery-hungry spinning platters of a hard disk, their high price and relatively low capacity can make them impractical for many notebook users.

Seagate is leading the move towards a new wave of ‘hybrid’ hard drives where a high capacity hard disk is partnered with a slab of solid state memory which automatically stores the most commonly-used files and data.

There’s also a growing trend towards lightweight operating systems which let you dive into email, browse the web and play music or movies without loading Microsoft Windows. Typically based on the Linux operating system and embedded into a flash memory chip inside the laptop, these ‘instant on’ systems spring to life within seconds instead of the hard disk-hammering (and power sucking) minute that Windows often demands – making them a boon for short work sessions on the go.

Those are some of the technologies now converging into the next generation of notebooks. Give us a few years, the experts say, and almost every laptop will be built for the long haul.

Introducing the Ultrabook

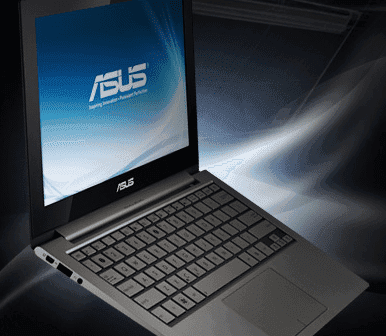

If you’re in the market for a thin and light laptop you’ll soon start to hear a new bit of jargon being tossed around. It’s the ‘ultrabook’ – a notebook which is ultra thin and ultra light.

Conventional ‘thin and light’ laptops have a waistline less than 2cm and tip the scales at under 2kg, but ultrabooks blast past the 2+2 recipe. They’ll typically have a ‘flying wedge’ chassis tapering to 0.5cm and weighing closer to 1kg.

The posterchild for the ultrabook movement is the MacBook Air, although you won’t hear Apple spouting the ‘u-word’ – it’s a term used by the makers of Windows notebooks. The typical ultrabook will resume instantly from sleep mode, use flash memory SSD chips rather than spinning mechanical hard disks, run for four-to-six hours and be priced at around $1,000.

That specification is a tall order against the price-tag . Notebooks with those spec sets have usually belonged to the ‘ultra premium’ category with a much higher price tag. However, Apple has demonstrated that it’s entirely possible to produce a laptop that meets these requirements, with the entry level 11-inch MacBook Air selling for $1,150.

The first Windows-powered ultrabooks, from Acer and Asus, should be on sale by the time you read this, with models from Dell, HP and Toshiba tipped to follow before the year is out.